Graeme Johnston / 27 December 2024

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), chapter VI

1. Introduction

In this article, I share some experience and thoughts about how to approach the topic of classifying work, experience, knowledge and other intangible thing in the legal world. I focus on four practical legal contexts within organisations which represent and advise people on their legal needs.

I’m going to distinguish two main types of organisation for this purpose:

- ‘provider’ – which I’ll use as shorthand for any provider of law-related services and products, regulated or not. For example, law firms, law centres, ABSs, ALSPs and online services offering practical legal help.

- ‘legal department’ – by which I mean any part of an organisation which looks after the organisation’s own legal needs, or buys external legal services, or both.

The article is not directed at educational, academic, legal research or philosophical needs. It is also not directed at computational law i.e. endeavours to automate legislation, contracts and other legal instruments. I have excluded these domains simply because their needs are in my view sufficiently distinct from the areas that I do focus that there is a risk of distraction at best, impairment at worst, if they are handled together.

2. Background

My thoughts about this topic have evolved over many years — in the 1990s and 2000s in the context of studying law, then working as a lawyer and writing about law; then in the 2010s and 2020s in the context of setting up and running a legal software company (Juralio), establishing and participating in the development of an open source community with legal taxonomy issues at its heart (noslegal) and doing various consultancy work for providers and legal departments. All these experiences, and many other conversations and things I’ve read or heard, have combined to influence my thinking.

Whatever you think of the latest round of AI, one thing that’s been interesting to observe in 2024 is just how many organisations it has motivated to express more interest in classification of data. The realisation is dawning more widely that, unless you define what conceptual definitions, relationships and distinctions matter to you, you’re going to suffer from the problem which the Cat expressed so pithily to Alice.

Over the next few weeks, in January 2025, I’m aiming to reflect on some aspects of this more deeply to help me contribute to some important new releases in noslegal (open source legal taxonomy and more) in 25Q1 –

- an update to the taxonomy facets which were released in 2022 and 2023

- a new taxonomy guide

To get my head properly back into it, I decided to write this piece in the calm of Twixmas 2024 to help me

- think about and articulate where I currently am on all this

- share that articulation in case it helps anyone grappling with what can be a daunting topic

- invite thoughts from anyone who cares to offer them (and which, practically speaking, I can feed into the noslegal work just mentioned)

Now, on to the substance of the article.

3. Four practical legal areas where classification is useful

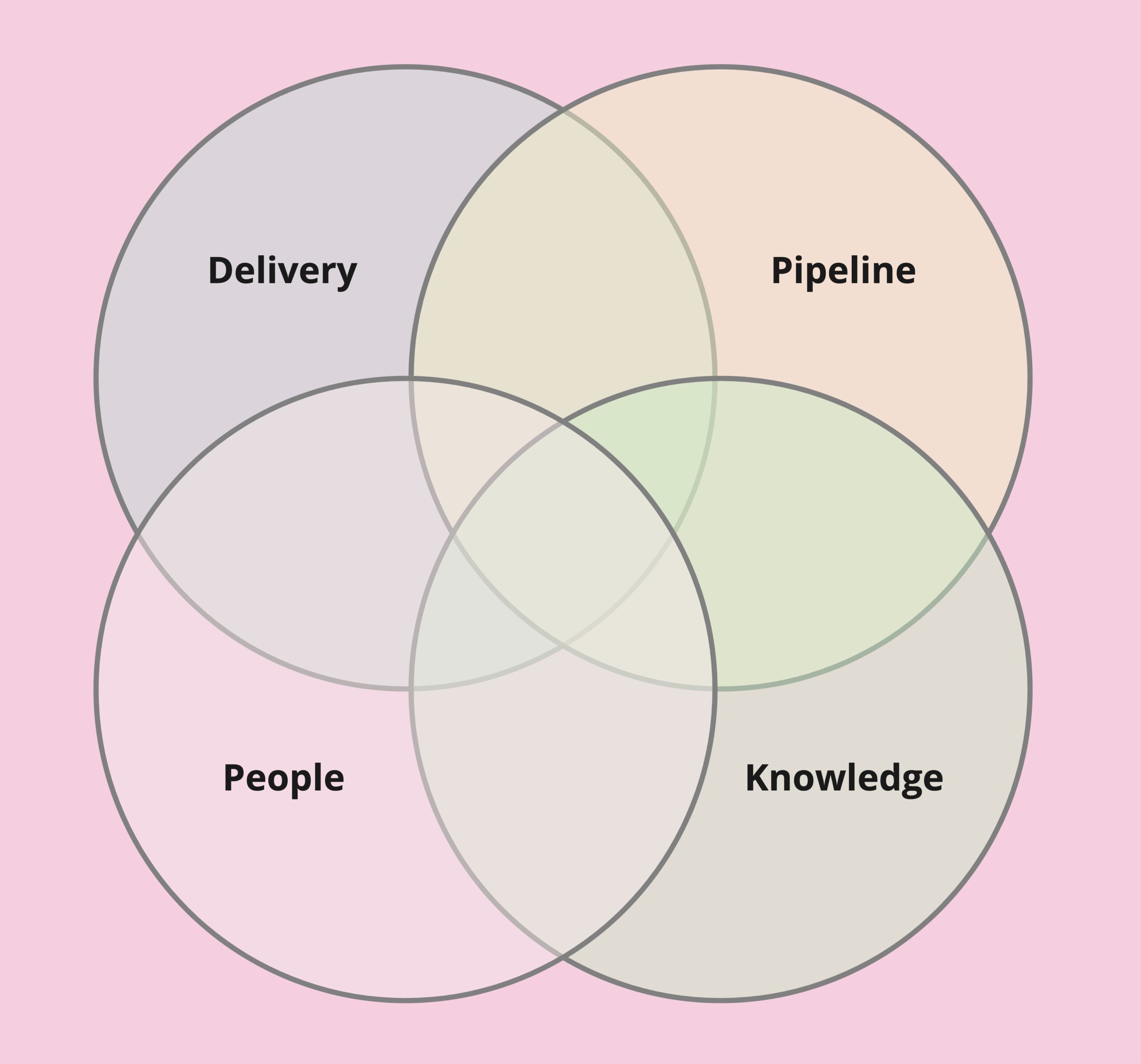

The illustration for this article summarises how I think of four overlapping areas of need in providers and legal departments. For succinctness, I’ve given them each a single word name.

- Delivery refers to delivering legal services, outputs, outcomes and products. It includes

- sourcing, doing and managing legal work

- preparing documents and other outputs

- budgeting and pricing the work or its outputs or outcomes

- preparing and reviewing invoices (an area which has spawned great complexity in recent decades for charges based on time spent)

- designing and implementing better processes to improve quality, speed and relationships (with team, client, provider)

- using technology and data

- Pipeline refers to upcoming work which a legal department is seeking to procure external legal help with and (from the other side of the fence) activity within a provider intended to help generate work.

- On the legal department side, this includes

- sourcing strategies – different types of provider

- engaging providers with insight into their strengths, weaknesses and suitability

- determining what work to handle internally and how to resource it

- On the provider side, a distinction is usually made between

- marketing – designed to increase awareness of a vendor’s offering and help establish its credibility – for example, writing articles, giving talks, sponsoring worthy causes, hosting events

- business development – commonly used in the legal world as a euphemism for sales

- On the legal department side, this includes

- People refers to the skills and experience people have or need. Articulating this systematically is useful in

- identifying people’s development needs – which can be met, for example, by suitable work allocation, secondments and training

- staffing work – by identifying people who have relevant experience

- identifying gaps in expertise for which the organisation should hire

- Knowledge refers to the desire which providers and legal departments have, particularly as they grow, to improve

- the records of what they have done factually, so that it can be built upon effectively later

- the ability of their people to benefit from knowledge otherwise contained inside the heads of individuals who eventually retire, leave or die, and who can only share manually up to point beforehand anyway, even where inclined to

- the quality and speed with which specific outputs can be generated

In practice, most of the knowledge actively curated in providers and legal departments, in so far as not inside heads, is currently captured in documents (in the broad sense e.g. including videos not just writing) produced deliberately

-

- as knowledge resources or

- for the purpose of advising or representing a client, but which can be repurposed as knowledge

But it also includes knowledge embedded in interactive software, for example for the purpose of generating documents or answers, or modelling a process. I expect that the data recording what people actually do — the processes they actually follow — will increasingly be a key type of knowledge in the years ahead. What people do, not just what they say.

4. Overlaps and distinctions

These four areas of need overlap and interconnect. In a law firm, marketing efforts flow (imperfectly) into business development, which flows into the delivery of work, which is staffed with regard to past experience, and which in turns generates experience for individuals and, if properly handled, knowledge and credentials for the organisation. Which can be used for further marketing, business development and delivery.

Shared concepts can help to invest proportionately and effectively in improving the firm’s approach to all these things, in a joined-up way.

Practical classification in a provider or legal department should, in my view, seek to distinguish between

- concepts which can usefully be shared across those four needs

- those which should only be elaborated within a specific context

For example, it’s clearly desirable to have a single concept of ‘arbitration’ across all four areas, but the finer issues falling within that concept may only be relevant in some areas. To take an extreme example, ‘enforcement of foreign arbitration award in China’ may be relevant for Knowledge and even some People purposes, if you have the system in place to apply it meaningfully; but it’s far too much detail for most* Delivery and Pipeline purposes.

A contrasting example is that sectoral subdivisions are often of more interest for Delivery and Pipeline than for Knowledge purposes, unless the particular sector has truly specialised areas of law associated with it. And if that’s so, the subdivisions of most relevance for Delivery and Pipeline purposes may not be the same as those for Knowledge purposes. Think of, say, Real Estate or Insurance as sectors and then as areas of law. And the aspects relevant for People needs will tend to be a mix of those various ways of slicing it – the ‘commercial’, the ‘getting things done’ (process) and the ‘legal’ if you like.

* Note (11 Jan 2025): The point has been made to me after publication of this article that, for delivery and pipeline purposes which are closely tied to knowledge, a more detailed knowledge-type taxonomy can be relevant. To build on the ‘enforcement of arbitration award in China’ example, a prospective client may want to know if your firm has experience of that particular work and, if so, the particular individuals who have done it before. These are search use cases – you’re trying to pinpoint something. It is true that more detail can help there, but a couple of observations are (1) in the delivery and pipeline context, for the more financial analytic / reporting types of use case, a higher level approach usually suffices, (2) if you’re classifying manually, you may not practically be able to classify matters or credentials to that level of detail, as practising lawyers often don’t care as much about correct classification as knowledge professionals, (3) a higher level taxonomy also suffices in practice for finding a lot of credentials and experience. If, for example, the high level taxonomy helps you quickly see that only 2 people in your firm of 200 people have experience in China-related arbitration matters at all, then you can filter down on them and their matters and search within those; or simply ask them. Now, over time it is foreseeable that you may be able to classify in more detail, as technology increasingly assists with classification. But the point is that taxonomy in law firms and legal departments at the moment tends to be a computer application-by-application topic, and you can achieve a huge amount of value in delivery and pipeline contexts with something simpler in your PMS and credentials software (for law firms) and vendor management software (for legal departments); and if your organisation doesn’t already have a good simple taxonomy, accurately applied, it should be your pragmatic priority in those contexts to sort that out first (which is non-trivial) before diving into great detail.

5. Mapping the four areas to organisational structure

Particularly in larger law firms, these four areas of need tend to map approximately to separate sub-organisations, each with a characteristic software application (or at least, a specialist Excel sheet!)

- Delivery in the sense discussed above is largely handled in a law firm by the lawyers and the finance / accounts department. The finance department will often have considerable responsibility for the taxonomy used to classify what types of matters are being handled in the firm, with the taxonomy being implemented in a law firm’s financial software (typically known as a ‘practice management system’) or in, the case of a corporate legal department, in specialist financial software used to review law firm invoices (‘ebilling’). In large law firms these days, there are often specialist roles such as pricing, legal project management, process improvement and innovation whose work sits in this area as well, though there is variation in precisely where they sit in the org structure. In large legal departments, especially in the United States, there are sometimes specialist roles known as legal operations which in practice tend to be quite focused on software (such as ebilling and contract lifecycle management) but often undertake wider activities as well.

- Pipeline tends in law firms to be divided between separate marketing and BD – business development (sales) functions. ALSPs may call BD sales! Marketing will typically operate a taxonomy centred on the website (though with other potential uses) and BD / sales will typically implement a taxonomy in a credentials and CRM system(s) used both for developing particular client relationships and for quoting the provider’s prior experience to support pitches for new work.

- People needs in the sense described above typically sit primarily with the lawyers doing the work, though some law firms have in recent decades sought to involve Human Resources more often, with a view to introducing systems designed to improve the mix of experience junior lawyers receive and to drive higher utilisation and financial recovery for the firm (for example, by identifying that lawyer A in office X has relevant experience and isn’t too busy so can help with a matter in office Y where everyone is already too busy). ALSPs will typically have a more centralised system for this from day one. Some large law firms also have specialist flexible working divisions via which external consultants (often but not always ex-employees of the firm) may accept particular assignments. Functions like this may or may not have a specialist software system: the use of spreadsheets appears to be quite prevalent.

- Knowledge tends to be handled in a law firm by library, information systems or knowledge functions, with specialist software for curating knowledge and making it available. People in law firms with some technical training in taxonomy usually sit here. ALSPs often have aspects of this, though under a heading such a process improvement. In legal departments, knowledge sharing often suffers from limited resources, though some are making efforts for example as parts of legal operations roles.

6. The prevalence of fragmented taxonomies

Over half a century ago, Mel Conway suggested that

organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations. We have seen that this fact has important implications for the management of system design.

Fred Brooks, a leading light at IBM at the time, called this Conway’s law. In medium and large law firms, it comes to mind when I see the separate taxonomies embedded in the separate computer applications for each sub-organisation operating in the four areas mentioned above. The separate taxonomies are often not particularly fit even for the purposes of that sub-organisation (for example, making distinctions of questionable relevance and clarity, failing to make more important distinctions). And as the needs of each sub-organisation are different, and taxonomisation is hard even for a single sub-organisation, there is usually little or no joining-up between the various taxonomies. Everyone is busy and everyone has their own local KPIs to meet. Unless there is a strong vision from the centre, or from sub-organisation heads who get together to improve things, the problems tend to persist.

A further complication is that, although the specialist business services functions in a law firm (finance, marketing, BD, HR, knowledge etc) tend to ‘own’ a particular software application and its taxonomies, the way the lawyers are organised (i.e. ‘practice groups’ or departments) cuts across this and tends to impose its own pressures, leading to challenges even within a single function’s taxonomy. As a simple example:

- Imagine a financially-driven (PMS or ebilling) taxonomy of matter types with concepts such as litigation or real estate.

- Also imagine that there is a specialist group of people within the provider or legal department who do real estate litigation work.

- If they sit in the litigation practice group then the matter types taxonomy will likely have real estate litigation as a subtype of litigation. If they sit in the real estate practice group, it will likely be a subtype of real estate.

- What then happens if there is a reorganisation with the real estate litigation team moving between groups? Or if two organisations merge and their respective real estate litigation teams are in different groups initially?

- There are plenty of more subtle examples. But suffice it to say that, when looking at a taxonomy which has accreted over decades without major redesign, it tends to reflect the organisational structure and elements of its history.

7. Entropy in practical legal classification schemes

“Smooth the descent, and easy is the way:

But to return, and view the cheerful skies,

In this the task and mighty labour lies.”

From Dryden’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, book VI

Another observation I have from seeing many taxonomies in medium and large organisations is that after some years or decades of being passed from one hand to another, they tend to become unruly. Concepts are added piecemeal when a gap is felt to exist, often without sufficient regard to what’s already there and the impact on the overall design. Superficially, it’s easy to do but slowly the mess accretes. And then the problem becomes even worse, as the totality of the scheme is hard to comprehend, and probably incoherent. Workarounds emerge, such as local guides or individual habits of choosing from only a few concepts because of the incomprehensibility of the whole.

In contrast, stripping away or refactoring concepts is tougher: it requires knowledge and judgement, it involves considerable work, the benefits and challenges may well not be understood by management, and it runs the risk of upsetting someone. And as the reasons for bad data are complex – going beyond classification schemes – and none of the solutions are easy, the topic may seem almost futile to embark upon addressing. Whatever the precise mix in a particular organisation, this factor is, in my observation, typically significant.

The good news is that it can be addressed with an effective strategy which involves tackling things in carefully thought-out stages, though always with one eye to the possible end state and another to the incremental delivery of value which can then be built upon in the next stage.

8. Other issues which contribute to bad data

In practice, problematic classification schemes are usually accompanied by weak processes, inconsistent practices and inadequate, or inadequately used, software for applying them to data in practice. The result is bad data which – depending on the severity of each of the multiple problems and the importance attached to resolving the problems – can be onerous or even practically impossible to ‘clean’ (i.e. better fit to reality).

The process, practices and software aspects are of great importance. As it happens, I’m quite engaged in them with my Juralio software and consultancy hats on. But for the purpose of limiting the size of this article I’m going to focus here only on the classification scheme issues. It’s all related though — for example, the more complicated your taxonomy, the more effort you’d better put into software, process and practices if you don’t want to increase your bad data risks. And if you’re starting off, it’s better to implement something quite simple but (crucially) extensible (able to cope with the addition of concepts without losing coherence or usability). Make that simple version work well first and deal with any problems before adding detail. Relatively coarse but accurate data is much more valuable than theoretically more detailed, but in reality less accurate, data.

9. What do we mean when we talk about taxonomy in this context?

So far, we’ve been talking about classification. But let’s talk about taxonomy specifically. Wikipedia has a decent introduction to the history and range of meanings of the t-word. But for practical purposes I’ve found that what’s usually meant by it in the practical legal world is

- a conceptual tree – concepts and sub-concepts

- a limited number of levels – usually low single figures

- with each sub-concept having one, and only one, parent

For example, litigation may be conceptualised as a sub-concept of dispute resolution. It’s convenient in practice to refer to simple lists of concepts with no subtypes as within the scope of the word ‘taxonomy’ (though hairs can certainly be split on this). The sort of simple taxonomy I’ve just described is much less ‘sophisticated’ than alternatives such as

- polyhierarchical taxonomies (i.e. hierarchical but each subtype can have more than one parent)

- ontologies (i.e. more flexible relationships between types – not just hierarchical)

But, I think a focus on simple taxonomies is appropriate because

- It reflects the realities I’ve seen in providers and legal department, both in people’s existing understandings and in the software applications they use

- For finance-related purposes in particular, the artificiality of putting everything into a single tree is extremely convenient and gives something that can be worked with, despite the gameability and other weaknesses

- As I go on to explain below, there’s a lot you can do with a simple taxonomy, handled effectively.

10. The magic of faceting

One problem I have seen with taxonomies in practice in law has been inadequate faceting. Let me explain this with an example. Imagine that your firm does a lot of employment-related work and you want to differentiate various types of employment matter

- Advice to an employer on changes in employment law affecting the retail sector

- Representing someone in an employment tribunal claim involving discrimination issues in financial service

- Advising a company on an investigation into allegations of harassment of employees in the software industry

- Advising a company on the employment law aspects of a transfer of business in a manufacturing context

One way to model that is to have a single list of matter types encompassing the various factors which have actually occurred or may occur. That quickly becomes a very long, unmanageable list.

Another way is to have different facets which can be combined. For example, lists of

- Types of process – advice, litigation, investigation, buy/sell transaction

- Sectors

- Legal specialisms – employment and perhaps some specialisms within it

Simply to illustrate the combinatorial arithmetic, with just three facets and ten types per facet — 33 concepts in total, including the facets — you can express 1,000 combinations (10 x 10 x 10).

Another major benefit of faceting is that you also reduce the problem of having the past — and people’s opinions on past, present and future — prejudging what might be relevant in future. You still have to show some judgement in choosing the concepts in each facet, but you don’t limit the combinations which in future may arise unexpectedly. And, at the advanced level, if you’re really determined to obtain good quality data, you can also figure out ways to test the concepts by watching which ones are chosen and which are not, and by gathering data on what other concepts people are looking to express.

Of course, everything in moderation: too many facets can, like everything else, become unreliable in practical contexts. And, all models being imperfect, you will sometimes have to make judgement calls as to which facet a particular concept should live in; and this may involve trade-offs. More of that in the financial and digital context, below.

11. The magic of levels

The hierarchical nature of a taxonomy has an attraction to the legal mind. Substantial legal documents such as textbooks and complex contracts tend to have a tree-like structure to assist comprehension and navigation. For example, a contract of even modest complexity will commonly have four levels, identified with a system along the lines of

- 1, 2…

- 1.1, 1.2…

- (a), (b)…

- (i), (ii)…

- (a), (b)…

- 1.1, 1.2…

In addition to human comprehensibility, sub-dividing can be very useful in the practical legal contexts discussed in this article:

- For reporting, process improvement and other finance-related topics, it allows for numbers to be rolled-up, drilled-down and generally managed in ways that help understand what’s working well in terms of finance and process, and where there is room for improvement.

- For search, browsing and filtering purposes (e.g. in knowledge, credential, website or experience contexts) it increases what can easily be found: for example, if I search for ‘Indonesia gold mining international commercial arbitration’ then it is practically helpful to search quality that Indonesia rolls up into SE Asia then Asia then Asia-Pacific, that gold mining rolls up into mining into extractive industry into natural resources, and that international commercial arbitration rolls up into arbitration then into dispute resolution.

A difference between these three purposes is that for the third, polyhierarchies and ontologies are valuable because of the more sophisticated semantic relationships which can be modelled, whereas for the first two the simplicity of a non-polyhierarchical taxonomy is superior. This is an example of how needs overlap but also diverge, and the points towards the central, higher-level approach being a non-polyhierarchical taxonomy even though specialist areas may enrich it where useful.

But there can be a risk of going too far with levels. For example, it is perfectly coherent to use seven levels – or even more – to map places

- EMEA

- Europe

- Western Europe

- United Kingdom

- England and Wales (a legally-relevant concept)

- England

- Plymouth

- England

- England and Wales (a legally-relevant concept)

- United Kingdom

- Western Europe

- Europe

However, it will likely not be practically sensible to do so in most provider or legal department contexts. If you are in a global law firm, for example, the upper levels of that example tree will likely be of more practical relevance to you; otherwise if you are a regional law firm with offices across south west England. And even if your organisation is, or may be, interested for some purposes in certain levels – say, the EMEA, Europe and Western Europe ones – then it may not be essential to bake it into your taxonomy if you can address it via reporting or search tools. A fairly simple taxonomy of two of three levels may well meet your needs even if sometimes you need to roll up to higher levels.

And bear in mind that places are fairly easy and unambiguous, aside from some disputed borders and sovereignties. In contrast, many concepts of legal and commercial relevance can be, and are, distinguished in different ways by different people in different legal systems and other contexts; and the boundaries between them are often fuzzy and the hierarchy more subjective. The more levels you have, the more you run into such issues.

12. Balancing simplicity and expressivity

To sum up so far, you have several tools at your disposal

- The facets which you choose to create

- The levels in each facet

- The concepts (typically known as categories or types) in each facet

- The software you use for classifying, the levels and facets it can cope with and the extent to which you can realistically expect good data from it (bearing in mind e.g. its user experience, who uses it and to do what)

- The processes and practices you have and the extent to which you can realistically expect good data from them

- The software you use for reporting and searching and the extent to which you can use this to remedy any weaknesses in your taxonomies

- The attributes you apply to

- things (such as documents and matters)

- clients, clients’ counterparties

- your providers (if you are a legal department)

- your team members

(These may permit you, for example, to infer certain links and prioritise or de-emphasise certain types in certain contexts)

- Whether you require something to have a single type (from a given facet) or permit it to have no, or multiple, types.

- For example, if you’re capturing experience and knowledge then the range of issues arising in a matter may be worth capturing, in some detail if you have the tech, processes and sustainable practices to do so; but for financial reporting it’s important to capture the primary type, at a higher level

How you balance these is very context-specific, but as a general rule try not to lean too heavily on any single tool. Spreading the load can be effective, though it does require having an eye to the whole system, and the needs within it, not just to particular elements of it.

13. Standardisation and its limits: core and extension

A pidgin… is a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from several languages. It is most commonly employed in situations such as trade… [A] pidgin is a simplified means of linguistic communication, as it is constructed impromptu, or by convention, between individuals or groups of people.

Wikipedia entry on Pidgin

The image which accompanies this article represents, very roughly, how the needs and relevant concepts in the four major areas may overlap, and how they may not. The reality is messier, and the relevance of particular concepts and needs varies significantly between and within organisations.

In my opinion, having considered a variety of practical problems and different organisational needs and demands in this area:

- It is realistic to aim for a common language – a pidgin, if you like – in the overlaps

- You risk problems if you specify it in too much detail

- Specifically, you risk over-fitting it to a particular area of need (e.g. knowledge), a particular country or some other specific context, and damaging its utility in other contexts

- By doing so, you therefore risk damaging the ability to join up data across those areas of need

- This risk is not theoretical: it is reflected in the mess of unlinked taxonomies which we have today

Striking a better balance in a way that works across many organisation types, countries and other contexts is not at all easy.

What we’ve tried to do in the noslegal project – which is non-commercial and permissive open source – is to identify some facets of broad relevance and some relatively simple core content for each. Core content is what we think is likely to be relevant across many organisations and across the four areas of need, though inevitably it will not be relevant across all such needs in all possible organisations. We’ve tried to limit the number of concepts in each core: ‘less is more’ is the guiding principle. We’ve also tried hard to ensure that cores are jurisdiction agnostic, though of course that’s not entirely possible.

We also have a concept of extension packs which allows for further detail to be expressed for organisations or areas of need in which it is relevant, without overloading the core for everyone else.

Keeping the core content relatively simple also allows organisations to adopt parts of noslegal and disregard our extension packs, instead extending it for themselves while maintaining a common language for their interactions with other organisations (e.g. law firms and companies working together).

That’s the design strategy. The main facets we currently have are

- Places

- Work — which means work in the process sense e.g. dispute resolution, transactions

- Sectors — we have taken NACE and therefore ISIC as a starting point but extended it in various ways of practical relevance in legal work

- Laws — that is, specialist areas of law

- Subjects – people, things, organisations, roles and relationships

- Information assets – for examples, documents serving different purposes – this is fairly high-level, at least for now (e.g. it doesn’t descend into the detail of different types of transactional documents and their components – and if we ever do in future, that will be classic extension rather than core territory for us)

In the current round of work, we are expecting to retire an existing facet (Perspectives) – distributing its content between Sectors and Laws – and to refine the others in various ways – some additions, some simplifications, other improvements (e.g. moving things between core and extension in light of experience and feedback).

We also expect to add a new facet – Processes – which contains typical plans (phases, work and outputs) in various Work contexts.

Organisations are free to use any of this material — it’s permissive open source (Apache 2.0 licence) so there are no strings. You can use it for whatever you want, amend it, even republish it as your own standard if you like (though you’re also welcome to speak with us with any suggestions for improving noslegal!) Practically speaking, in so far as you stick with at least the core elements without changing them, that also gives you the benefit of easily tracking and incorporating any future refinements we make to noslegal in light of our community’s experience and feedback. Whereas if you heavily modify it and effectively create something new, you own it for better and worse when it comes to future maintenance.

14. Accommodating alternative approaches without creating a muddle

Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity

John Punch’s 17th century summary of William of Occam’s philosophical razor

One topic which comes up quite a lot is that organisations want to position the same concepts differently in their trees, either generally or for some specific purpose.

A simple example is that ‘Data protection and privacy’ in the noslegal Laws facets released in May 2023 is a subtype of ‘Information law’ – which also contains intellectual property, defamation and reputation, freedom of information and other topics. Is this a useful way to organise it? I and others think so. Is it the only way? Certainly not.

This sort of issue arises in various contexts. The reality tends to be complex, but three common threads are:

(1) Accept the noslegal hierarchy as good enough, on the basis that the advantages of a standard outweigh the benefits of doing it another way. You can still extend it (i.e. adding more levels, facets or both) to meet your own organisation’s specific needs. You can also, consistent with this approach, ignore noslegal extension packs and, indeed, whole facets or parts of facets (e.g. a corporate legal department will commonly have no significant need for family law concepts). And you can report in different ways even within a certain taxonomy e.g. to pull concepts in from different trees.

(2) Depart from the noslegal hierarchy, for example by splitting out intellectual property in the example above. But retain the noslegal concepts. This gives you most of the advantages of standardisation though, if exchanging data with another organisation (e.g. between client and law firm) using out-of-the-box noslegal you’ll need to bear in mind that your trees are different and do some mapping – which inevitably has some cost and risk.

(3) Do your own thing and just take inspiration from noslegal but depart as you see fit, splitting or defining concepts differently. Again, a perfectly legitimate strategy but you won’t get the future benefits of standardisation in terms of updates and data exchange.

Option (3) can be the path of least resistance in a large organisation, but you might consider (1) or (2) depending on your vision of how things are likely to play out.

Another issue which sometimes arises is how to conceptualise financial services and digital technology, as these often cut across the main sectoral lines of relevance in a matter. For example, in an energy sector M&A context, you may wish to capture that there is a particular type of financing involved in addition to the energy sector and the M&A process.

It is tempting to address this by extending concepts within noslegal’s Work and Law facets, for example. But it’s worth looking at the whole system and thinking of ways to do it more smartly. For example, if you give clients and counterparties in your system sectoral attributes then the involvement of private equity may be seen from the connection of those parties with the matter. Alternatively, you could create a separate attribute for your matters to capture financing type in addition to the main sector (e.g. energy) and only allow entries from a particular part of a larger facet. As usual, there are trade-offs in terms of expressivity and complication and it rather depends on your organisation’s context.

These are just examples. The bigger point is, when presented with such conundrums, think around the options that you have, and aim where possible for one which uses the tools you already have. Don’t just plump for the lazy option of creating new concepts without identifying other possibilities and weighing their pros and cons in your organisational context.

15. Improving your taxonomy over time

One of the challenges of managing a taxonomy is to develop it in a nuanced and relevant way by reference to changes in the relevant importance of things over time. Simply observing how people actually classify things with your taxonomy is obviously inadequate, as that doesn’t tell you what’s missing or misconceptualised. You’ll need to step outside that closed world and try to find out what people are really doing and thinking about classification needs, and deploy some practical insight into what distinction are likely to be useful for a particular purpose. This includes talking with people who are in a position to know: in my experience, people actively involved in cleaning up bad data are often the best ones to talk to about this, though it’s important to check with people from many different perspectives if you can.

One of our challenges in noslegal is that, although some participating firms have kindly shared (in confidence, with working groups) some internal material, which gives some insight into different conceptualisations, we are mostly limited to data which has been published. We have sought to make the most of this, for example, by analysing how many firms conceptualise their services on their websites, but have been quite reliant on human insights and judgement.

Within a large organisation, you have potential to do more right away. You can institutionalise ways of regularly speaking with people with different perspectives and capturing their ideas systematically. You can give them easy ways to make suggestions for improvement (e.g. within computer applications they use every day) and capture these. You can look at what they search for in relevant computer applications. You can analyse reports made internally and to clients which involve manipulation of data (e.g. mapping a law firm’s taxonomical types to a client’s types). Over time, you can gradually identify more resources which can provide insight into the distinctions people make for practical purposes.

16. Possible uses of AI

That last point brings me to what the latest round of AI, based on language models, can contribute to all this. That’s a big topic, and I don’t want to over-burden what’s already quite a long article, but I would suggest three big areas.

- Taxonomy development. Consider the final lines of the previous section, about using an organisation’s data to improve your taxonomy. There is potential to apply AI here to analyse what may otherwise be an overwhelming and ever-developing volume of data. With skilled human oversight, I can see that becoming really valuable.

- Better application of taxonomy to data. Applying taxonomies to data is a major challenge at present. At the moment, the main tools for addressing this are process (e.g. when and from whom do you seek and update classification), practices (assisted by education on the why, what and how) and software (with user experience playing a major part). One practical problem at the moment is that the boundary between concepts is not always clear from the name alone. Definitions and examples are helpful to disambiguate, and we have provided many within noslegal. But getting the people who properly understand what a matter or document is about to read such definitions and classify the matter thoughtfully can sometimes be challenging in organisational realities. Pointing an AI tool armed with definitions and examples at documents can likely help with this at low (document) level. Conceivably, pointing it at a large mass of material on a matter (for example, documents, time entries, structured tasks) may also help to classify the matter itself and even to cast light upon the nuances of its internal content, for example particular workstreams for phases.

- Using the better data. There are also numerous uses for better-classified data, many of which will likely benefit from AI, among one of many techniques. But I won’t scope-creep this article by listing them.

17. Concluding thoughts

How we organize our world reflects not only the world but also our interests, our passions, our needs, our dreams.

David Weinberger, Everything is Miscellaneous (2007)

There is much more to this topic than can sensibly be covered in a short article written in a short time, but I hope that this has been an interesting and – if you’re a practitioner in the field – useful piece.

I remain committed to developing and sharing thinking on this topic in public via noslegal, and any comments or other contributions prompted by this article will be most appreciated. Let’s improve things together.