Graeme Johnston / 10 February 2023

This is the first in a series of five posts discussing time recording in legal services. The intended topics are:

1) Setting the scene – the history and current status of time-recording practices – this post, Fri 10th Feb 2023

2) Different types of pricing and target – appearance and reality – Fri 17th Feb 2023

4) How might wider changes (world, society, economy, organisations, gender, process, technology…) affect things? – Fri 3rd March 2023

5) Conclusions – scenarios of continuity and change – Fri 10th Mar 2023

Introduction

Discussion of time recording in legal services — and of its progeny, time-based pricing and billable hour targets — can be more than a little frustrating.

Critics have, for many years now, emphasised its negative effects on clients, lawyers and society more generally; and on its tendency to stifle attempts to improve matters.

Such criticisms are weighty. But big questions always arise for me, such as

- What is really going on, anyway – how far does time-based billing currently apply? What are the trends – how is it expanding, contracting, mutating?

- How do we separate talk (‘what would be nice’) and shallow surveys (‘AFAs you have encountered’) from what’s actually happening?

- What are the needs which this system meets and can they be met acceptably in other ways – and at what cost?

- What does ‘better’ really look like? Is it, like Churchill’s observation about representative democracy, the worst system except for all the others that have been tried? At least for certain kinds of legal work.

- Are pricing models such as fixed fees, subscription fees or purely success-based fees likely to remain in specific niches, or will they become more generally applicable?

Recognition that there may be a problem is not new. To put it mildly, time recording is not a neutral act: ‘you get what you measure’ is a cliché for a reason. But major change has proved harder. For example, a report by a commission of the American Bar Association (ABA) over 20 years ago (2002) listed many of the system’s corrosive effects while also articulating why it has remained so entrenched – this US summary gives an idea of it, as does this UK one. (I’ve read it in the past but it’s so old now that I can’t even find a full free-to-read version online.) Time-based billing and targets have been challenged in various ways (more on that later) but the reality, so far as I can tell, they remains powerful default approaches.

My intention over this series of posts is to set the scene (this post), explore the current reality (post 2), its implications (post 3) and some forces which may – or may not – lead to change (post 4) then to wrap up with some conclusions (post 5).

My idea in all of this is not to offer definite predictions, or a single recipe for addressing a complex topic, but to offer some points for thought in making sense of current realities and future possibilities. If you’re in a position to do something about it, I hope you find it helpful – and let me know what you think and of the aspects I’ve missed.

But before all that, this first post seeks to summarise the history of how we got here – at least in the US and UK – I think this is important in casting light on the needs which the time recording model meets, and which any replacement will have to meet if it is to succeed.

Heber Smith’s system: the early years

Systematic, granular time recording in legal work seems to be about a century old.

- By ‘systematic’ I mean where it’s the normal, permanent, presumed way of doing things in an organisation, rather than an exception.

- By ‘granular’ I mean time-recording down to the level of an hour or even smaller unit of time. I’m going to use GTR to mean granular time recording in this sense.

GTR’s principal early promoter, Reginald Heber Smith, appears to have started work on it first in the 1910s (when organising legal help for the poor in Boston) then in more depth from around 1920, after he joined a New York business law firm and convinced his colleagues to record time.

However, Smith did not widely publish his method until 1940 and it seems not to have become dominant until the 1960s in America; and later, and to more varying extents, elsewhere.

Lawyer time-recording is best known these days as a basis for time-based pricing. However, one of the key talking points of today’s time recording software vendors is that, even as departures from pure time-based billing become more common, more detailed time recording is still worth optimising as a way to better understand how people are spending their time in order to give management the ability to do x, y or z in response. The website of Smith’s old firm has a valuable summary, written in 2009 and evidently based largely on a memo he wrote in 1966. From this, it is clear that Smith’s original aspiration was to use what we would today call ‘big data’ for varied management and process improvement purposes. ‘Taylorism’ in the jargon of those days. As an indication of the spirit of times, the U.S. Chief Justice was already complaining in the 1930s about the emerging large law firms as ‘a new type of factory, whose legal product is increasingly the result of mass production methods.’ (Galantar and Paley, Tournament of Lawyers, 1991, p17).

There is no indication that Smith’s original motivation was to promote time-based pricing. However, he and his firm appear to have ventured down that path at some point before 1940, perhaps in stages as the business logic of each step impelled the next.

Smith’s 1940 encapsulation

In my beginning is my end.

T.S. Eliot, East Coker, 1940

In seeking to understand how time-based billing became a dominant model, it is illuminating to read Smith’s four part series ‘Law Office Organization’ published in the American Bar Association Journal in 1940. You can read it for free on JSTOR.

There is much value there, including on the breakdown of tasks and their allocation to appropriate staff. Lessons still not fully learned to this day.

However, for present purposes the important point is the emphasis placed by Smith on two specific needs which could be met by time recording.

- The first need was pricing: to cover unpredictable costs and still make a profit. Specifically, a law firm’s costs (partners’ drawings, staff salaries, rent) are largely time-based yet, Smith observed, it was often unpredictable how much of the time in question will be spent on a particular matter. In Smith’s own words (from part 2 of his 1940 series):

If you ask an architect how much it will cost to build a house, he cannot give even an estimate until he has seen all the specifications. No client can give to the lawyer comparable specifications. For example, neither can then tell how much of a fight the opposing party intends to put up. If you beat him in the trial court and he accepts the verdict, that is one thing, but if he is determined to appeal, that is another.

The fact that the US litigation system was chosen as an example is perhaps revealing.

- The second need emphasised by Smith was reward: to measure relative contribution for the purpose of determining pay within a partnership. Smith expresses this as a ‘quota’ in $ terms but then, crucially, states (part 3):

Now we can take the next step. The lawyer with the $5,000 salary has a quota of $10,000. He has to earn $10,000 and he will try to do so by selling his time. Every man is expected to work a standard number of hours a year.

The series concludes by explaining how three factors (hours spent on client work, the amounts billed and the gross profits generated) can be analysed to ‘arrive at a judgment as to each lawyer’s worth to the firm.’

Smith admits that hours recorded, and the other two metrics, are ‘substantial’ rather than ‘conclusive’ evidence of contribution but suggests them as a simple way of prorating credit between partners while avoiding ‘ad hominem’ argument.

The imperative for a managing partner of a growing firm (as Smith was by that time) to figure out an efficient way of minimising pay disputes is apparent.

Smith certainly should not be regarded as a simplistic solutionist. To quote again from his 1940 writing:

all the qualities and values of a lawyer cannot be caught in a statistical net no matter how finely spun… But the question is, what better method is there? It is impersonal, it is open and above-board, it does yield a vast amount of information….

Nevertheless, as his old law firm observes (in the 2009 piece):

Extrapolated from one firm to an entire industry… and fueled by forces that he could never have foreseen, Smith’s formula for fairness and efficiency was to become something else altogether.

Smith’s system goes big

The use of time recording data as the basis of a pricing model seems to have been adopted by various leading Manhattan firms in the 1940s.

Time-based billing evidently became the norm in American firms in the 1960s, assisted by

- promotion of the practice by the American Bar Association to its members starting from 1957/8, the financial success of which is celebrated in this 1966 statement

- requirements for minimum fees imposed by state bar associations from the late 1940s

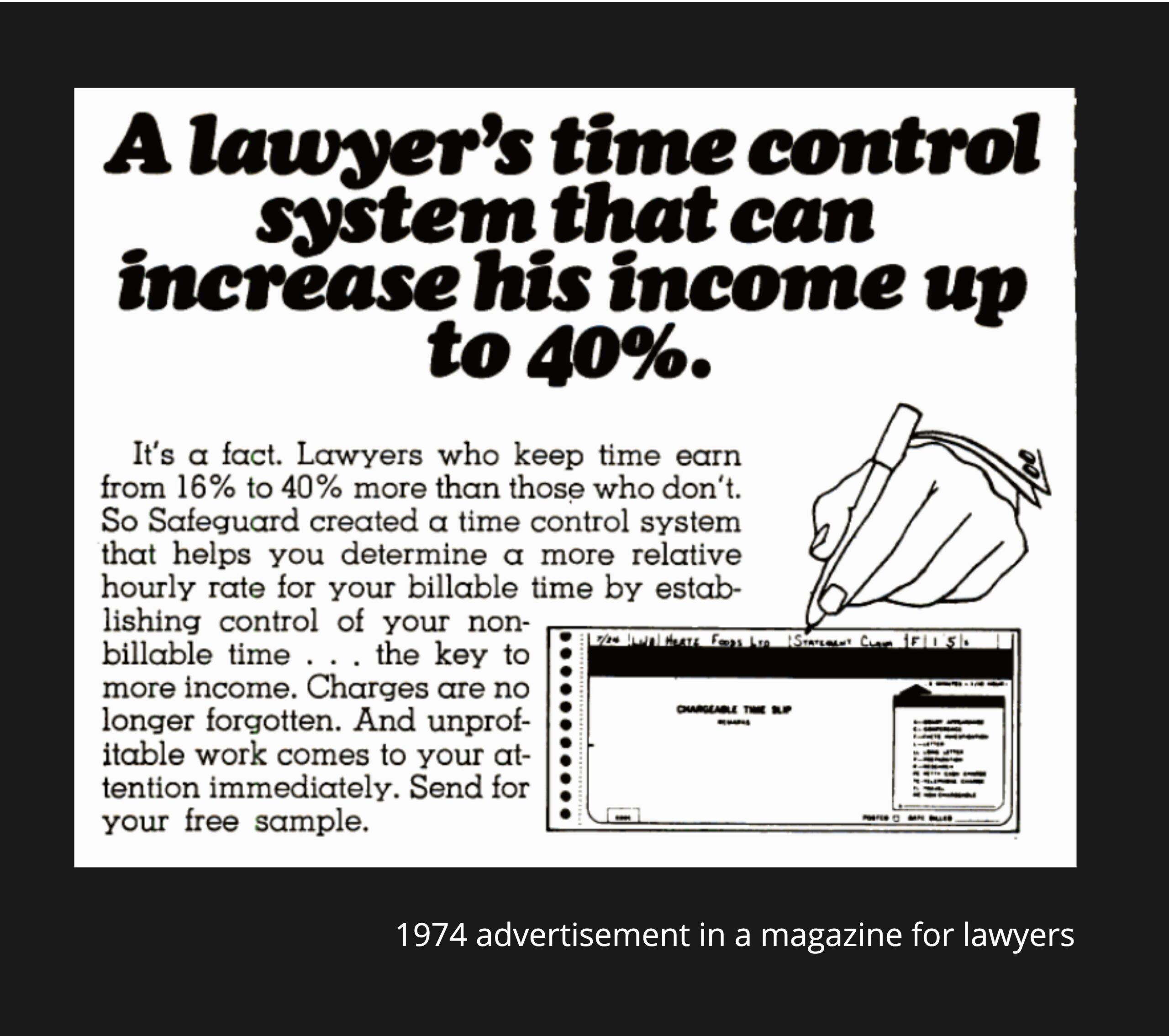

Approach 2 was struck down by the Supreme Court in the 1970s as an illegal price-fixing cartel, but by then the practice of time-based billing was entrenched as a driver of profitability. Look at some ABA Journal advertising from the early 1970s on Google Books, such as the example at the head of this article. In some ways it feels like a different world (lawyers are still predominantly ‘he’) in other ways it’s very familiar (highly precise ROI % range). But it seems fairly clear that time recording, and billing based upon it, are being presented as already a proven model. The impression is of gadgetry being marketed, by that time, to relatively late adopters. And soon after that, early computerisation of law offices naturally helped this along.

As regards billable hour targets, it is revealing to note how little the basic numbers have changed over the years –

- Smith’s 1940 article reported annual billable hour targets in his firm of 1,600 for associates and 1,520 for partners (dropping to 1,200 for the over 50s who are expected to devote more time to charity and public services, while also prudently slowing down).

- There is evidence of billable hour targets already rising to around the typical current level (1,800–2,000 hours) in leading US firms by the end of the 1960s. (Tournament of Lawyers, pp 34–5).

The last few decades

When I started law firm work in New York in 1994 then London in 1995, time recording was still done via the weekly paper grid invented by Smith, still running on his original decimal unit system (1 unit = 0.1 hours = 6 mins) – though the numbers handwritten into this grid were then entered into a computer by someone else. Time-based billing was also, by that time, the general rule.

Speaking to people with longer memories, it is clear that there was a significant lag, in London at least, between the introduction, first, of time recording in the 1970s and 80s, then of time-based billing as the default rule. Perhaps around 15-20 years behind America. But, as in Smith’s own firm in the 1920s and 30s, it seems that one thing led to another.

These days, the United States accounts for around 50% of worldwide legal services spend, with the UK second at around 5%. Time-based billing is significant in both of these and also in many other anglosphere / common law countries. So far as I can tell, it has also become more common in many civil law countries though not yet as widely as in the anglosphere. Really good data is, again, missing or at least not known to me, but it is at least clear that there is a very substantial amount of work still being done on a time-spent basis.

To keep things manageable, I am going to concentrate on the US and the UK in the following posts. There are similarities but also some important differences between even these two. But I hope the points covered will be of wider interest as well.

Alternatives to time-based billing

Time-based pricing has been challenged in various ways from the buyer-side. One approach which started to become significant in the 1980s, led by GE among others, was to create more extensive in-house legal departments.

Major efforts which started to become prominent from the 1990s – with some later refinements, and some ebbs and flows in prominence – include

- so-called ‘alternative’ pricing or ‘AFAs’ (alternative fee arrangements) – some straightforward but others more complicated and raising problems (various traps, differences between appearance and reality and some unintended consequences)

- attempts to create more of a sense of competition among law firms (e.g. by more formal procurement and panel processes)

- exploration of alternatives to law firms (legal process outsourcing / managed legal services / ‘New Law’ etc)

- better technology for data-gathering and analysis (e.g. ‘ebilling’)

There have also been some regulatory and seller-side efforts, though there are some counter-currents as well (e.g. passive time capture technology pitched to law firms as, naturally, an opportunity to capture and bill more time).

The reality so far as I can tell is that, in most contexts in which time-based pricing had become the norm by the 1990s, it is still significant. That said, it is more important in some places and types of work than in others. In some areas it has expanded, in others it has contracted. But appearance and reality can be hard to untangle.

More on that in the next post.

Notes:

- This is an updated version of an article I wrote three years ago, published here. The next four posts will be substantially new though, as my thoughts have developed over the last three years.

- Title of article inspired by Macbeth’s time soliloquy.

- Image from advert at page 1503 of volume 60 of the American Bar Association Journal – December 197