Graeme Johnston / 10 February 2022

I’m intrigued by this week’s announcement by the largest English regulator of lawyers (the SRA) that, while it recognises that legal work can involve long hours and heavy workloads, it will now consider taking enforcement action against law firms in serious or persistent cases of ‘imposition of wholly unreasonable workloads or targets’.

The lack of clarity makes me suppose that not much is going to happen by way of enforcement against major firms in the short term, but it’s interesting to see the topic of hours and workloads now on the agenda as a distinct regulatory area of concern.

This follows the October 2021 New York State Bar Association Attorney Well-being Taskforce suggestion of capping lawyer billable hours at 1,800 per year. That’s much more concrete than the SRA’s concept, but doesn’t yet have regulatory force.

The rest of this article discusses the issue and speculates how things might realistically play out.

Working hours in UK law firms

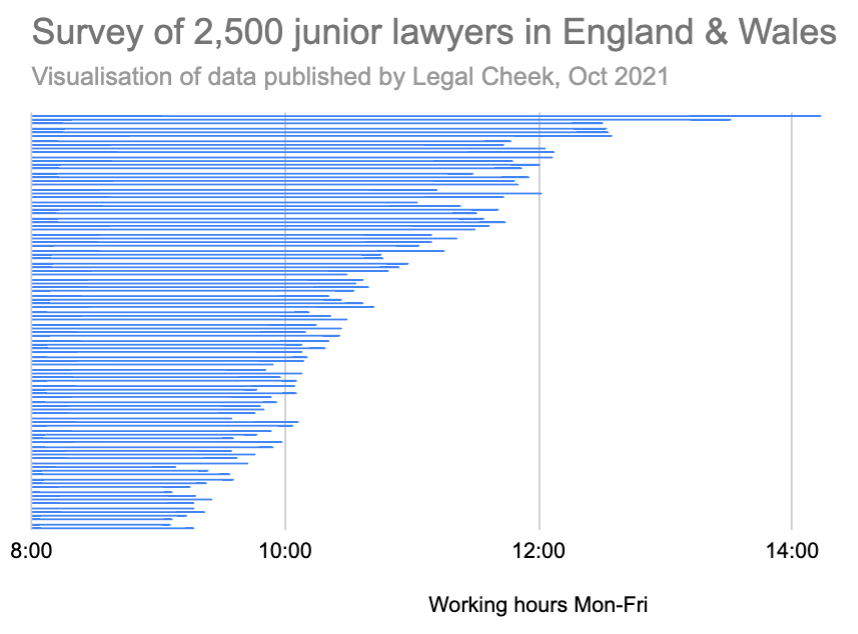

It’s well known that many law firms have a long hours culture. As an illustration of the realities, the image at the top of this piece is my visualisation of Monday to Friday working hours shown in this survey of 2,500 junior lawyers in England & Wales in 102 law firms, published by Legal Cheek in October 2021.

It’s worth noting that the numbers captured in the survey are start and end times, implicitly assuming a clear working day. My visualisation simply captures the delta between them. Some of the survey responses published by Legal Cheek note that some people also work on weekends and out-of-hours. The concept of a clean break from the working day has, notoriously, been under increasing challenge for lawyers and others with the advances in mobile technology over the last twenty years. Working from home over the last two years seems likely to have exacerbated the problem for some people, by blurring boundaries.

Broadly speaking, I doubt that the general picture revealed by the survey will be hugely surprising for anyone familiar with the UK law firm market. The eight firms with the longest average hours are all US law firms in London, for example. At the other end of the spectrum, the shortest working hours are most common among firms outside London. The survey confirms rather than surprises.

Is there a problem?

Views vary as to whether this is a problem and, if so, how big, whether fixable and, if so, how.

I think it’s fair to say that it’s not traditionally been taken seriously as a problem in the world of large London law firms. I base that on a lot of things I’ve heard and read over the years, but also on my own experience, which I don’t think is exceptional.

My own experience

I qualified as a lawyer with a large London firm in the late 90s, as a litigator. There was a working-into-the-evening culture but it wasn’t extreme. All-nighters were only required occasionally, in genuinely exceptional cases, such as emergency injunctions.

This was in contrast to my experience as a trainee lawyer working on corporate deals – that had a very late-night / all-night culture as the juniors were essentially left to sort out various aspects of the legal details after days of conference calls led by bankers. I felt it was an unhealthy culture – nothing to do with the particular firm or individuals, something broader in the London corporate finance world.

As regards underlying cultural assumptions, I remember that when the EU 48 hour working week law first came into force in the UK, in 1998, we were immediately presented by management with an individual opt-out form to sign. The expectation was clear.

In my own little bubble of City of London lawyer-think at the time, the idea of working hour limitations had a certain continental-social-democratic vibe. The history of the UK government’s resistance to EU regulation of this topic in the 1990s, and its role in the historic 1997 election, is quite interesting.

I guess my working week in those days must have been around 60 hours on average Monday-Friday, not counting commuting time or the occasional weekend. But it was fine, and there was always the consolation that working longer hours meant more billable hours, and that was well understood to be a crucial metric given its close link to revenue.

At least in those days you could switch off more easily, as laptops and mobiles weren’t yet standard, certainly not at junior associate level.

Outside the law bubble

As well as moving forward in time, let’s zoom out from the legal world for a minute.

In the UK as a whole, there is credible evidence that millions of people feel they are over-working. It also seems clear, when you compare the UK to other countries, that the UK’s relatively long working hours don’t translate automatically into productivity, though the reasons are contested. Here’s a sample analysis by the TUC in 2018 but there are others. So far as I can tell, the reality of how many people feel about it isn’t seriously contested, though the appropriate response certainly is.

I’m not going to rehearse all the arguments pro and con. Suffice it to say that:

- It is clear that excessively long working hours can be problematic for individuals, as well as a source of risk for a law firm and its clients. These things have, in fact, been accepted in other jobs (e.g. driving trucks and flying planes) for years.

- It doesn’t take a genius to work out that there’s a diversity implication if people’s prospects depend materially on working really long hours.

Why is this so difficult to address?

Long hours culture in law firms is particularly challenging to address because it’s baked into the business model. A driver of profitability. And in a highly fragmented market with high transparency as to profits per partner and a great willingness of partners to move, the pressure on management to maintain and improve profitability is huge.

One theory which has been talked about for years now is whether “alternative fee arrangements” (AFAs) will change this. That’s law-code for fees not based solely on time. The term “value-based billing” is also used.

Outside the specialist world of contingency fees (a % of damages recovered in certain kinds of litigation), AFAs are typically fixed fees for a deliverable, a fixed retainer for a period, or a time-based fee with a cap, though there are some more complicated variants.

Although survey evidence is unsatisfactory, my best attempt to summarise the state of play is that:

- Usually AFAs means fixed fees or capped fees, or something closely related.

- Despite all the talk about value-based billings, most AFAs still have a strong link to recorded time. For example, fixed fees of any economic importance will mostly be agreed based on an estimate of the time required to deliver the work.

Where does leave things for law firms?

- Maintaining profitability matters. A lot. Though the numbers depend on the particular market niche you’re in.

- The link between time worked and profitability is strong, and difficult to break.

- In basic numerical (spreadsheet-y) terms, the four main levers that can be pulled to increase profitability are:

- The ratio of equity partners to other people whose time can be charged

- The achieved rate per hour

- The cost per hour

- The number of hours billed per individual

- The first three are hard to manage at individual, day-to-day level, so the temptation when you need to “make your numbers” (billable hours, actual billing, recovered cash) is to maximise the fourth.

Time-linked business models have implications

I mention all this because I think it’s important to realise that the kinds of solutions to over-working that may be viable in other industries may be even more challenging for organisations such as law firms whose revenues are highly linked to time spent.

For example, some companies in the video game industry are notorious for having a “crunch culture” – of which over-working is a significant part. Their product is linked to time spent in a general sense, in that the scope and quality of a game will be influenced by the attention given it. But the link is far less direct. 1,000 hours spent on a large matter for a law firm client may well translate into something close to double the revenue of spending 500 hours on the matter. Not so with games and many other products.

So, in the case of games companies, it’s possible to see in principle how the issue might be fixed with better management. This is reflected by the care which some software companies have been able to take to improve work-life balance while still being highly profitable.

If you read up on Scrum, for example, a widely used framework for software development, you’ll see that the emphasis is on sustainable, healthy hours for individuals as well as on productivity. The tension which many people see as inherent can in fact be resolved in work which I think can fairly be regarded as at least as complex and unpredictable as high-end legal work.

Would a billable hours cap work?

The SRA’s standard does not have any clear metric. Perhaps it’s just an ice-breaker and more will come in time. The NYSBA’s idea of capping billable hours seems to me to be a decent, simple, policeable idea. The cap could be applied over a reasonable period, whether the 17 week period used in other UK law contexts or a bit longer.

It could no doubt be gamed around the edges (we’re dealing with people whose jobs involving doing things with rules) but I can imagine a robust system if it’s based around such a simple rule. Certainly a billable hour cap seems a better idea than a working hours cap, for which the workarounds would be trivial.

With a billable hours cap averaged over a reasonable period, law firms would still be able to manage short term spikes in work, but over the longer term they’d have to choose between hiring more people or refuse work.

Wider benefits for clients and society?

There would also perhaps be a greater motivation to find more efficient ways of delivering work and figuring out how to make progress on loosening the link between time spent and pricing. And to improve processes, ways of working and use of technology. By removing the easy option of just working, and billing, more hours. In other words, it could benefit clients and society as well as lawyers.

There’s no free lunch, so who would lose out? There would potentially be some lowering of profitability at the top end but, really, would people at that level notice? Perhaps some reduction in the race-to-the-bottom that is a long hours culture would be appreciated there as well. And the lowering of profits is not inevitable, anyway.

Whether law firms can get their heads around all this is another question. I can imagine instinctive cries of outrage from some even if a regulator is brave enough to propose it.

Without a cap, what else could drive change?

- SRA enforcement on a subjective concept such as “wholly unreasonable workloads or targets” without a numerical cap. I doubt it.

- Firms being prepared to moderate profitability when their peers are not. Unviable, as it will predictably lead to departures threatening a firm’s viability.

- Enough people refusing to work in that culture to bring about a systematic change. Maybe, but I suspect there will still be many even if recruitment targeting has to shift.

- Major clients being prepared to switch most of their high-value work to new types of provider. There continues to be lots of talk about it, but I’m not aware of it happening at scale. Who knows, but in-house lawyers have challenges of their own to deal with and it can’t be easy to justify shifting work on this basis.

- Increasing alternatives for the kind of work that’s at risk of leading to overwork. That’s already happening, and I think is likely to continue up to a point, but I also suspect there will remain important categories of work for which market forces alone won’t fix it.

Conclusions

At the end of the day, I think the current system has problems that may not be fixable by market mechanisms alone. But which could conceivably be helped by regulation along the lines of the NYSBA proposal.

So I think it’s good that a more official level of conversation about it has started, however cautiously.

As to where it ends, I’m not holding my breath, as the idea of regulating this topic in an effective way feels culturally almost unthinkable in the US-UK legal context.

That said, regulation of minimum wage levels met similar resistance in the 1990s but now is an unquestioned part of the UK system and widely recognised as beneficial in mitigating an element of competition that is harmful to individuals and society.

In short, market failure is a ‘thing’, and well thought-out regulation can help address it in suitable cases. Maybe this is such a case. Worth thinking about, I would say.