Graeme Johnston / 18 January 2022

Let’s assume that you’re working on a project with many other people. A project that’s complex, in the sense that there are lots of moving parts, and success depends significantly upon adaptation to developments (for instance, the actions and inactions of people outside your team).

Two of the big challenges are

- staying sufficiently on top of developments in the areas that really matter

- turning that understanding into effective, coordinated action

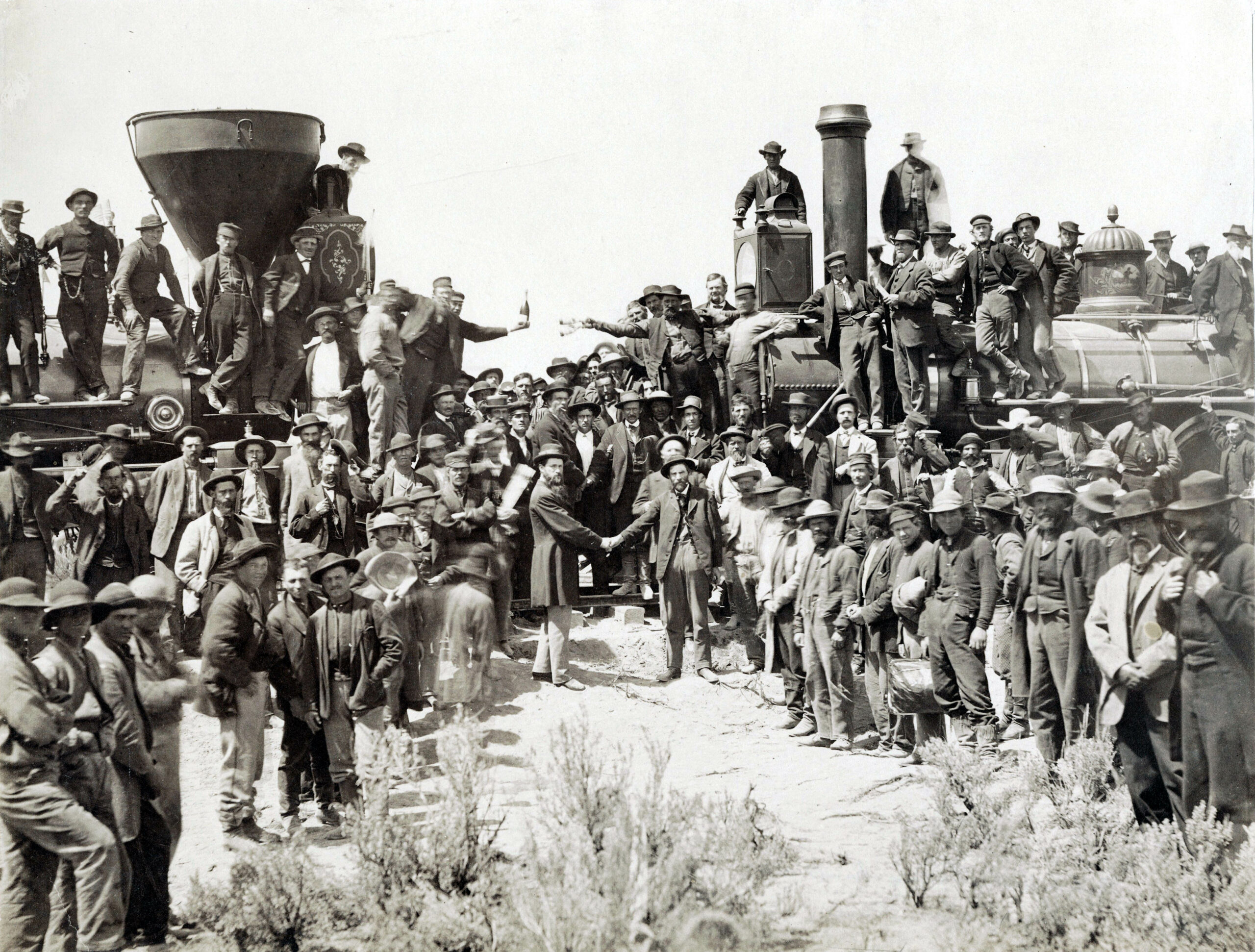

There are many aspects to addressing this – culture, people, processes, tools, budgets, contracts, timetables and more. However, an important, and in some ways counter-intuitive, insight was clearly articulated more than 150 years ago in the context of a very practical, successful organisation. The rest of this article briefly summarises the main points.

Your organisation, objectives, technology and attitudes are likely to be very different, in many ways, from the context in which these ideas were articulated. But some important things, I think, remain constant. I find that the value of reading about an older approach is that the distance somehow helps to see today’s challenges more clearly.

Summary

The approach taken by the organisation in question is well-documented, but the most approachable, shortish, free-to-read modern English language summary that I’ve found on the web is by Stephen Bungay in this 2011 piece in the European Financial Review.

It’s worth reading in full, but just a few of the points seen so clearly in 1869 were:

- The instinct in organisations running such projects can be to seek to control team members tightly by detailed rules and decisions. In fact, it works better for managers to display restraint and a certain simplicity in instructions.

- Managing things in too much detail undermines the morale of the team, reduces their ability to respond effectively when things don’t turn out as planned. It also distracts and over-works the manager.

- Instructions should specify what is to be achieved and why, but should leave the how to the implementing team.

- Such instructions should succinctly contain everything that the implementing team cannot determine for themselves to achieve a particular outcome. And no more – that’s where the discipline and judgement really come in.

Done well, in Bungay’s words:

The result is that the organisation’s performance does not depend on its being led by a… genius, because it becomes an intelligent organisation. Rather than relying on exceptional individuals, this solution raises the performance of the average. Being able to adapt to circumstances, the organisation will tend to make corrective decisions whilst executing even if the overall plan is flawed. In effect, [they] turned strategy development and strategy execution into a distinction without a difference.

I deliberately haven’t mentioned names so far because I think it’s more helpful on first acquaintance to make things a little more abstract.If you’re not already familiar with the history, I wonder if you can guess which organisation it was. The answer is, of course, in the article already mentioned.

Reflections

Clearly much has happened since 1869, including (thankfully) more legal and other constraints on the “how” of projects. But these basic insights from the 1860s are reminiscent of approaches which have developed since the 1980s in response to the ineffectiveness of more basic forms of management. Many modern examples could be given, but if you’re familiar with concepts such as Agile project management or OKRs, I’m sure you’ll see the similarities.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing, then, is that the basic insights have been around for so long but are still not widely understood, or well applied, in many organisations. The familiar combination of chaos, authoritarianism, gaming-the-system, siloes, perverse incentives, tech-and-process-primitivism and other dysfunctions. Of course, the org discussed in this article had its issues as well – to say the least – despite its effectiveness in getting certain things done.

Anyway. As the original author from 1869 says in his work (the full text of which you can read in, for example, this book), the worth of such principles

lies almost entirely in their practical application. What counts is to comprehend in good time the momentarily changing situation and after that to do the simplest and most natural things with steadiness and prudence.

If you found this interesting, here are three things to consider reflecting upon:

- How have human attitudes, expectations and projects changed – or not – since 1869, in ways relevant to this topic?

- How has technology changed the game? Which things are more predictable or able to be automated; and which are not?

- In your context, where is the line best drawn today between the “why” / “what” and the “how”? Big topic.